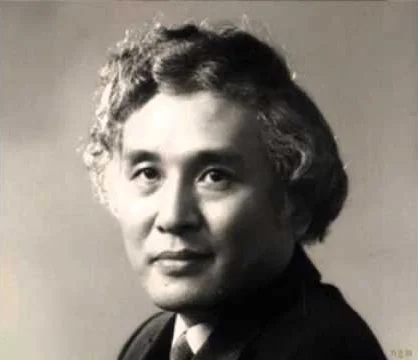

TOSHIRO MAYUZUMI (1929 - 1997) – Mayuzumi wrote two unnumbered symphonies. His first, Nirvana Symphony (1958) for male chorus and orchestra was recorded in the early 1960s of which I, somehow, acquired a copy [I was into things Japanese in those days]. I can’t remember much about the music except that it was very percussive, like his contemporary, and the more famous, Toru Takemitsu. The only really clear memory I have of the work is of the men’s choir/Buddhist monk style of chanting which made the piece interesting to me. Fortunately, the Nirvana Symphony is now available on YouTube with several recordings to audition; and I have used the opportunity to renew my acquaintance with the work.

Being too young to actually fight in World War II, after the end of the war, Mayuzumi entered the Tokyo National University of Fine Arts and Music where he studied music composition. He then went on to the Paris Conservatoire where he came under the influence of the European avant-garde, especially the music of Edgar Varèse. On returning to Japan in the early 1950s he launched a long, illustrious career in film scoring, composing the music for over one hundred feature films, including for several films that achieved international “hit” status [Tokyo Olympiad (1965) and Reflections in a Golden Eye (1967)]. He composed two operas [Kinkakuji, premiere Berlin 1976; Kojiki, premiere Linz 1996], three ballets, over twenty works for orchestra including a concerto for xylophone, chamber works for various instruments including electronic sounds, and a sizable number works for concert band for which he reportedly especially enjoyed composing.

But it is his mid-life decision, beginning in 1957, to put aside Western avant-garde composition techniques in search of a proto-Japanese sonority for his work that I find of greatest significance. Japan has an especially rich musical culture spanning many centuries, with an aesthetic that is incisive, clear and vital. Its pared-down, bare-bones frugality is not actually that much different from the very best in modern Western aesthetics and actually was a major source for that aesthetic. After all, it is no mere accident that haiku has become the most popular form of poetry-composition in many languages throughout the world, including in American English. Mayuzumi’s Japanese sources are abundantly clear, and what he does with them reveals the true dimensions of his talent.

The Nirvana Symphony is built on the sonority of Japanese Buddhist temple bells. The score presents their sounds in myriad ways, from distant to feeling like you are actually inside those bronze giants that require for sounding a sizable log clapper swung against it from the outside. Mayuzumi uses a bell reference in the naming of the movements, as follows:

Campanology I (instrumental)

Sū ram gamah (with male chorus)

Campanology II

Mahāprajnāpāramitā (with male chorus)

Campanology III

Finale (with male chorus)

The entire first movement explores the bell sonority in extraordinary ways using primarily the string, wind and brass instruments of the orchestra to recreate the initial ictus of the sound and its sustained dying away. Yes, there are numerous percussive sounds to help the effect, including such old reliable standbys as the vibraphone, tubular chimes, tam-tam and piano. He supplements these sounds with the use of actual temple bells, from bowl-size to large gongs. There is no sonata first and second theme groups here; or exposition, development or recapitulation. There is just the sound of the bells. But that does not mean the movement lacks organization. This movement functions, as does in actual Buddhist monks chanting and meditation, to free the mind of day-to-day concerns so that it might then enter into meditation. And the music accomplishes this imperceptibly, gong-stroke to gong-stroke, in a most extraordinary way, levitating and suspending the mind with the floating sonorities of the instruments.

By the time the solo singers enter at the beginning of the second movement the listener has shed the periphera of the moment and is prepared to receive the word. Japanese Buddhist monk chanting is a phenomenal aural experience. There is a logic to how it is done, but the “accidents” of many voices moving within an approximate parameter produce harmonies encountered nowhere else and are truly a marvel to behold. Gone are the major/minor modes of the West. Instead, the vocal line takes its direction, expression and rhythm from the word, the Japanese word. Mayuzumi could have transcribed the pitches and rhythms of the chanting directly from actual monks. It sounds very authentic. Or it could all be original composition “in the style of” Buddhist monk chanting. Whatever the case, it has the feel of the authentic, including passing moments of touching expression, exactly like the model. There are frequent harmonies of a minor third that fall but sadly on the Western ear. One might speculate it falls similarly on a modern Asian ear, now attuned to Western-derived popular music. Plus it is, after all, being performed by a symphony orchestra.

Next follows alternating movements for instruments (bell sonorities) and male chorus with the last movement depicting the passage into nirvana. I certainly do not know this from any translated text from the Japanese, since none it provided on the internet. I do not recall whether my 1960s-era l.p. had translations of the text. I doubt that it had since no lingering understanding of what’s being said remains, which surely would have if there had been a translation, even after so long a time. No matter! The music makes it abundantly clear what’s happening. After a tumultuous preceding passage, the chorus enters quietly with a gently melodic upward-rising phrase that can only be about one thing. And slowly the symphony comes to a majestic conclusion amid a carilloning cacophony. And the listening has been a real experience. There is a unity to the expression that is impressive. Those bell sonorities throughout the entire score resonate with a complex aural beauty. The musical logic, while seeming to have no logic, is rock-solid: I have been to that place, have meditated on the Eternal Soul, and have returned exhilarated by the experience. What more can we ask of a piece of music?

To hear a recording of the Mayuzumi Nirvana Symphony go to

YouTube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TYbkf2w3neY Tokyo Metropolitan Symphony Orchestra, Tokyo Philharmonic Chorus; Hiroyuki Iwaki, conductor

Mandala Symphony (1960), in two movements, is not of the same high compositional caliber as the Nirvana. Scored for large orchestra, it is built on Japanese Buddhist mandala symbology. Without a score for reference, I can’t be sure the work is built on a tone-row – that is, the method of composition using twelve tones devised by Schönberg – but it sounds like it is. Unfortunately, it carries with it the mannerisms of the tone-row composers and consequently suffers from the association. Again, there is the sonority of the temple bell, but the sound fails to be sensual or impressive as it is in the earlier symphony. The movements are titled as follows: I Vajra-dhatu mandala: Tempo non equilibre; II Garbha-dhatu mandala: Extremement lent. The first movement suffers most from pointillist mannerisms. I find little to commend it. The second movement is more successful in capturing sustained bell-like sonorities and the extreme slow flow of high court music [Bugaku]. There are also several violin solos of some delicacy and expression. I suppose, if one is especially captured by the Nirvana symphony, one owes it to oneself to give this work an airing, too.

To hear a recording of the Mayuzumi Mandala Symphony go to

YouTube Part I: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zKlk_gZR4cs Part II: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=e29nHw-ago8 NHK Symphony Orchestra, Hiroyuki Iwaki, conductor (1960 recording)

I would also like to point the way to several other of Mayuzumi’s orchestral works that have their own appeal – his Bacchanale of 1954 and the ballet Bugaku of 1962, both of which can be found on YouTube. Mayuzumi has a real gift for transforming traditional Japanese music into modern orchestral sonority and often dances skillfully between the two great traditions. Bugaku is especially rich with felicitous examples of this. I consider it in the same class as those early ballet scores by Argentinian Ginastera.

To hear a recording of the Mayuzumi Bugaku go to

YouTube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OJAUsJ_HJTQ New Zealand Symphony Orchestra, Takuo Iwasa, conductor

Is Mayuzumi the first great Asian symphonist? The Nirvana Symphony makes a good case for its creator. Perhaps if he had written more symphonies, or if the Mandala had been on a consistently high level, I might be more inclined to throw my lot in with him. Historians view Mayuzumi as being in the shadow of his better-known contemporary Toru Takemitsu, but I have never found anything in Takemitsu’s music approaching the delights I find in Mayuzumi’s. I guess the telling thing here is that I am considering him at all for the distinction. I will not hesitate, however, to designate the Nirvana Symphony one of the great symphonies of the century and worthy of serious attention.

from "On the Symphony in the 20th Century" by Jerré Tanner - a book surveying over 250 symphony composers and their works, many of them forgotten and no longer performed, composed in the 20th century that are worthy of the listener's attention.